Developed by a team of former Google employees, Toit is a complete IoT platform with remote management, firmware updates for fleets of devices with features similar to the one offered by solutions such as balena, Microsoft Azure, or Particle edge-to-cloud platform.

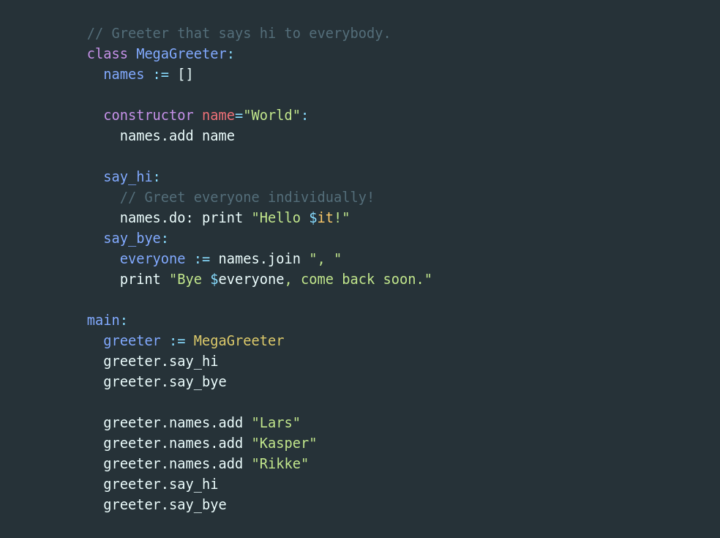

Toit currently works on ESP32 microcontrollers using lightweight containers, and after seeing existing high-level languages MicroPython and Javascript were not fast enough on low-end microcontrollers platforms, the team at Toit started to develop the Toit language in 2018, and has just made it open-source with the release of the compiler, virtual machine, and standard libraries on Github under an LGPL-2.1 license.

One of the main reasons to switch from MicroPython to the Toit language is if your application is limited by performance or you operate ESP32 from a battery, as Toit claims up to 30x faster performance with Toit on ESP32:

We went into crunch mode and some months later, we had the first results. We were executing code more than 30x faster than MicroPython on an ESP32 with a high-level language that abstracts away memory allocation and that can be learned in a few hours by a Python developer: the Toit language.

So let’s have a deeper look by trying it out in Ubuntu 20.04. The virtual machine is based on a fork of the ESP-IDF with custom malloc implementation, allocation fixes for UART, and LWIP fixes. That’s what we’ll need to install first:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

git clone https://github.com/toitware/esp-idf.git pushd esp-idf/ git checkout patch-head-4.3-3 git submodule update --init --recursive export IDF_PATH=$(pwd) popd |

Now install ESP32 tools:

|

1 2 3 |

sudo apt install python3-pip $IDF_PATH/install.sh . $IDF_PATH/export.sh |

and build toit and samples to run on the host machine:

|

1 2 3 |

sudo apt install go --install=classic sudo apt-get install gcc-multilib g++-multilib make tools |

We can now run the hello world sample:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

// Copyright (C) 2021 Toitware ApS. // Use of this source code is governed by a Zero-Clause BSD license that can // be found in the examples/LICENSE file. main: print "Hello, World!" |

as follows:

|

1 2 |

build/host/bin/toitvm examples/hello.toit Hello, World! |

That’s all good but what’s about building the sample for ESP32? Easy:

|

1 |

make esp32 |

This will create a Toit firmware file (toit.bin) preloaded with the hello world sample and that can be flashed with esptool:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 |

LD build/esp32/toit.elf esptool.py v3.1-dev Merged 2 ELF sections To flash all build output, run 'make flash' or: python /home/jaufranc/edev/esp-idf/components/esptool_py/esptool/esptool.py --chip esp32 --port /dev/ttyUSB0 --baud 921600 --before default_reset --after hard_reset write_flash -z --flash_mode dio --flash_freq 40m --flash_size detect 0xd000 /home/jaufranc/edev/toit/build/esp32/ota_data_initial.bin 0x1000 /home/jaufranc/edev/toit/build/esp32/bootloader/bootloader.bin 0x10000 /home/jaufranc/edev/toit/build/esp32/toit.bin 0x8000 /home/jaufranc/edev/toit/build/esp32/partitions.bin make[1]: Leaving directory '/home/jaufranc/edev/toit/toolchains/esp32' |

Good, but surely we can check a sample with Wi-Fi, and indeed there’s the http.toit sample:

|

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 |

// Copyright (C) 2021 Toitware ApS. // Use of this source code is governed by a Zero-Clause BSD license that can // be found in the examples/LICENSE file. import net import http main: network := net.open host := "www.google.com" socket := network.tcp_connect host 80 connection := http.Connection socket host request := connection.new_request "GET" "/" response := request.send bytes := 0 while data := response.read: bytes += data.size print "Read $bytes bytes from http://$host/" |

That neat and simple example simple download Google page and reports the number of bytes downloaded. But wait… Where do we configure Wi-Fi credentials? This can be done at build time:

|

1 |

make esp32 ESP32_ENTRY=examples/http.toit ESP32_WIFI_SSID=myssid ESP32_WIFI_PASSWORD=mypassword |

or you can change the default program and configure the WiFi SSID and password in the Makefile:

|

1 2 3 4 5 |

# Use 'make ESP32_ENTRY=examples/mandelbrot.toit' to compile a different # example for the ESP32 firmware. ESP32_ENTRY=examples/hello.toit ESP32_WIFI_PASSWORD= ESP32_WIFI_SSID= |

I do not have an ESP32 up and running to test it out, but I’d assume you’d be able to modify the hello.toit on the device itself after flashing Toit firmware the first time. OTA firmware update should be enabled too based on the output from the make esp32 command. The complete Toit platform is free to use for up to 10 devices, and besides the Github page, you can also find additional information on the documentation website not only about the firmware and Toit language we’ve used here, but also the Cloud API and Toit platform as a whole.

Jean-Luc started CNX Software in 2010 as a part-time endeavor, before quitting his job as a software engineering manager, and starting to write daily news, and reviews full time later in 2011.

Support CNX Software! Donate via cryptocurrencies, become a Patron on Patreon, or purchase goods on Amazon or Aliexpress

Thanks for mentioning the free and open source Toit language. If you build your firmware on top of it, you will still be using Espressif’s esptool to flash it into your device, so your compile-flash-run workflow will be similar to how it works with the widely used ESP-IDF framework. You will, however, write your code in a memory-safe and efficient high-level language, which is the main selling point for lots of developers.

Do let me know if you have any further questions!

I previously looked into this language, but I felt the overhead from learning a new language to high.

Also, the “compile-flash-run” workflow is pretty much useless doing anything more complicated than reading sensors and sending som post request. Not sure why you’d need to run “30 times faster than python” for these use cases.

How do you debug an application using the Toit language? I could not find any mention in the documentation.

What was the rationale for creating a whole new language instead of creating a faster MicroPython/Lua/Go compiler/interpreter for MCU? Using the same syntax allows reusing existing libraries.

would have been interesting to compare the performance vs usual C++ too!

Not sure there is a cpp API for esp32, but as I said in my other comment: comparing performance is basically pointless, because the use cases where theses languages skulle be used don’t really need to be fast – the development. Quick and dirty, nothing production worthy

Ah well espressif idf or arduino ide are C++?

and it’s not really the dev performance i am interested, but code size and execution speed, since those are the limiting factors, but yeah, just for reading sensors, its polntless,…

I Esp idf you can choose to code in c or c++, and its al works quite well, i see no reason to invent another language.

I use C to code on esp32. Micropython is a toy to me. I suspect Toit would be as well.

This

I don’t know why so many negative comments. Not all work is just “dirty development”, for small DIY projects, or smaller professional projects, where developing in c++ is expensive and unnecessary, and micropython consumes too many resources, this is a great solution.

I have to take the time to test it in the next couple of weeks!

Not only MicroPython or C/C++. There is also Lua (NodeMCU) and TinyGo.

So is there just in time on device compilation or is it only precompiled byte code? Is that why it is 30x faster or was it compared to precompiled micropython bytecode?

“that can be learned in a few hours by a Python developer: the Toit language.” … I’m a Python programmer, but Toit looks quite strange to me.

“The complete Toit platform is free to use for up to 10 devices” … ok, and what above 10 devices? License fees? What prices?

I did not go into details because that post is mostly about the Toit language, so there’s no need to pay anything if you’re not using their cloud.

But to answer your question, they charge $0.50 per serviced device per month when more than 10 devices are used with the Toit platform.

As far as I understand the language and runtime are available under LGPL v2.1, which doesn’t make any such restriction.

Arduino supports all kind of hardware to control actuators, sensors, displays, etc – there are hundreds of them.

The reason Arduino have out-competed other micro-controller ecosystems is because some heroic people read datasheets and wrote libraries for Arduino rather than for other platforms.

Python has some device libraries too.

Those libraries are community-tested and most of the time pretty reliable.

How about Toit?

I can see only a very rudimentary stuff. If you need anything beyond “Hello World”, be prepared to read datasheets and re-invent all the wheels and be a guinea-pig tester of their code. Be prepared that your software development beyond “Hello World” will be 30x slower than on Arduino or in Python.

“Hello World” is 30x faster than Python, though. Incredible!

I seem to be seeing a lot of unfairly negative comments.

While I don’t like complicated languages like Python that require a web browser constantly loaded on StackOverflow and that do not even resist to copy-paste, there are already some devices in field relying on these. And I think that encouraging developers to move to more energy-efficient languages is good in general.

The “30 times faster” argument is not the right one in my opinion, most people do not care about execution time. They should instead advertise “does the same using 30 times less power”, or “30 times longer battery life”. This is much more of a selling argument for IoT. Recharge your battery every month instead of every day without having to learn C! Or maybe further, add a tiny solar cell that will be enough to compensate for the small consumption.

If those using scripting languages can accommodate to this one, why not give it its chance ?

The thig is that C is the most energy efficient programming language (apart from ASM), so it is almost impossible to beat it. Rust is close, but no cigar.

I’m not speaking about trying to beat it nor even come very close, just be reasonably efficient. There’s always some static consumption, and the way peripherals are used on an MCU, or the device is put to sleep, count a lot as well. The time it takes to resume and suspend as well. And the time spent in the low-level system primitives as well. So if overall a moderately efficient language maintains the whole product’s efficiency within 20-30% of the optimal situation it’s not that bad, and in any case it’s much better than being 30 times less efficient.