The first time I used IPv6 was in 2000 for my final year project, and for many years, we’ve been told that IPv4 32-bit address space was running out, and a transition to 128-bit IPv6 address was necessary, and would happen sooner rather than later. Fast forward to 2017, I’m still using IPv4 in my home network, and even my ISP is still only giving a dynamically allocated IPv4 address each time we connect to their service. Based on data from Google, IPv6 adoption has only really started in 2011-2012, and now almost 20% of users can connect over IPv6 either natively or through IPv4/IPv6 tunneling. But today, I’ve read that IPv10 draft specifications had been recently released.

What? Surely with the slow adoption of IPv6, we certainly don’t need yet another Internet protocol… But actually, IPv10 (Internet Protocol version 10) is designed to allow IPv6 to communicate to IPv4, and vice versa, which explains why it’s also called IPMix, and it derives its names from IPv6 + IPv4 = IPv10.

IPv10 was created as it was clear that both IPv4 and IPv6 would still be in use for decades to come, but with the Internet of Things, a large number of IPv6-only nodes would come online with still the need to communicate with IPv4 nodes. Existing workaround such as native dual stack (IPv4 and IPv6), dual-stack Lite, NAT64, 464xlat and MAP, either do not allow for IPv4 to IPv6 communication, or are inefficient.

So IPv10 aims to address those shortcomings as described in the draft specs:

It solves the issue of allowing IPv6 only hosts to communicate to IPv4 only hosts and vice versa in a simple and very efficient way, especially when the communication is done using both direct IP addresses and when using hostnames between IPv10 hosts, as there is no need for protocol translations or getting the DNS involved in the communication process more than its normal address resolution function.

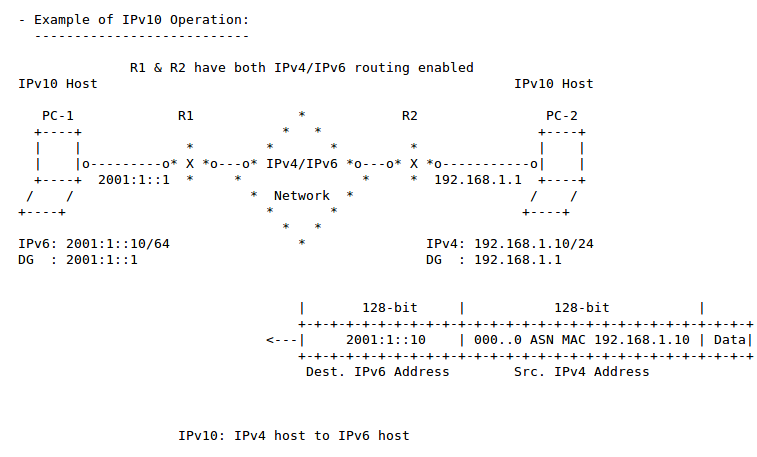

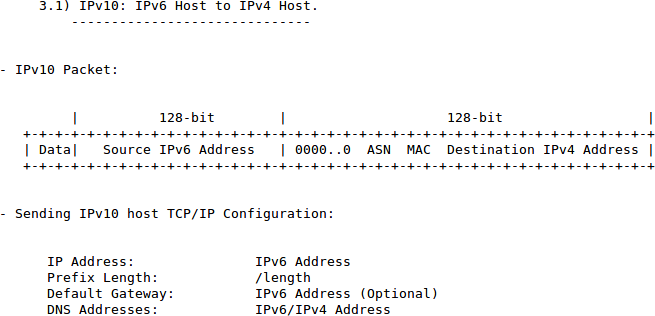

IPv10 allows hosts from two IP versions (IPv4 and IPv6) to be able to communicate, and this can be accomplished by having an IPv10 packet containing a mixture of IPv4 and IPv6 addresses in the same IP packet header.

From here the name of IPv10 arises, as the IP packet can contain (IPv6 + IPv4 /IPv4 + IPv6) addresses in the same layer 3 packet header.

IPv10 handles all 4 types of communications IPv4 to IPv6, IPv4 to IPv4, IPv6 to IPv4, and IPv6 to IPv6. You can read the draft specifications for details about the packets.

Jean-Luc started CNX Software in 2010 as a part-time endeavor, before quitting his job as a software engineering manager, and starting to write daily news, and reviews full time later in 2011.

Support CNX Software! Donate via cryptocurrencies, become a Patron on Patreon, or purchase goods on Amazon or Aliexpress

I’m lost a bit on what this solves. Legacy IPv4 systems do not generate this IPv10 header

And IPv4 addresses can be used in IPv6 addresses (by using a 0:0:0:0:0:FFFF prefix)

and there is 6to4.

If you need to change anyway then why invent a new variant. Why not go to IPv6?

@FransM

Based on the speces, It looks like IPv10 is for routers and Internet gateways.

IPv4 node <-> IPv10 router 1 <-> IPv10 gateway(s) <-> IPv10 router 2 <-> IPv6 node

So you can still have your IPv4 and IPv6 devices communicating over IPv10 without having to change anything.

So it’s like NAT but without the fixed port forwarding stuff?

I’ve read the entire spec and it’s IMHO ridiculous as it attacks the wrong problems by creating new ones. The first reason of low deployment of IPv6 is lack of incentive. Your home appliances don’t use IPv6 because it’s pointless since your ISP will not support it. And your ISP doesn’t care about investing money to maintain a full blown IPv6 infrastructure since people don’t have any IPv6 appliances at home. This is what has fossilized IPv4. And yes I do have IPv6 at home and it has even helped me quite a few times.

Here he’s proposing to wait for 20 more years for his new IP protocol to be specified, implemented, debugged, attacked, fixed and deployed everywhere. Also he reproduces some design mistakes of IPv6 : flow label is useless and wastes 20 bits (cf RFC7098). NextHeader is a gross design error that makes IPv6 headers unparsable by those who don’t know the exact size of all possible 256 header types since there’s no length information. TCP was smarter at this as it prefixes them with a length. Addresses contain MAC addresses (which remain a pain in IPv6 on the server side), and even has provisions for ASN (easier routing but will not be known in advance).

So in the end, he will need to have IPv10 enabled in a contiguous chain between the client and the server so that the last hop may decide to transform the protocol to IPv4/IPv6 (without knowing it’s the last one). Clients will not use it not knowing if the frames will get dropped by lack of infrastructure support. Server side will not enable it by lack of hardware support forcing them to disable all hardware acceleration. Infrastructure will not enable it by lack of users.

That’s exactly how you add a 3rd implementation of something when trying to converge 2 existing ones.

I think it would make more sense to encourage to natively *route* ipv4-in-ipv6 to real IPv4 addresses so that IPv6-aware clients have higher chances of reaching IPv4 hosts and that IPv6 on the client side is no more a dead end.

What were they thinking?! “After 20 years IPv6 is still deployed too slowly, so let’s come up with yet another protocol to de-focus from IPv6”

As @willy says “The first reason of low deployment of IPv6 is lack of incentive.”. Indeed.

Maybe that incentive will change if/when the price for IPv4 addresses rises (currently about 10 Euro per IP address). If not … so be it … let the market decide.

And, yes, I have IPv6 at home and on my VPSes.

I don’t totally agree, this does not pretend to substitute anything, it’s just a container with a translator between IPv4 IPv6 masked as a new protocol, but it is not. The inexistent headers in the IPv4 mean nothing since IPv10 will create its own header, and the translation will be done in a different way than NAT64, hence more efficient. In other words, this is just a faster workaround than the current solution, so it’s welcomed.

Anyways, I hope by the end of this decade half of the devices / providers in the world start to take IPv6 as a standard. Maybe I’m too optimistic lol…

Start reading (and laughing) here: https://www.ietf.org/mail-archive/web/ietf/current/msg100261.html … the author, and the reactions.

@Sander

hmm. I’ve learned a few things @ https://networkengineering.stackexchange.com/questions/44010/is-ipv10-a-joke-or-a-serious-rfc-draft:

1. IPv4 through IPv9 are already reserved (although only IPv4 and IPv6 are used). IPv10 is the next available unassigned version

2. Anyone can submit proposals to the IETF, and they are taken seriously, until they are either adopted or die due to lack of interest.

@cnxsoft

And how is the IPv4 system supposed to put the IPv6 destination address in the packet header ?

@Jean-Daniel

Yeah, it would need to be modified… The draft paper also reads:

So that’s probably non-starter, that things is DOA, as mentioned by others here, and other places.

@cnxsoft is correct. This is a proposal by an individual. The IETF allows anyone to propose anything. There have been past proposals for new math that “proved” that 2+2 != 4, for example.

Unfortunately, this proposal also self-assigns a version number (10) – even though IP version numbers are assigned much later in the standards process, only when there is sufficient community support within the IETF for the development of a new standard. The proposal is now being called “IPmix”, FWIW, to avoid that problem.

If you have questions for the author of this document, you should contact them directly.